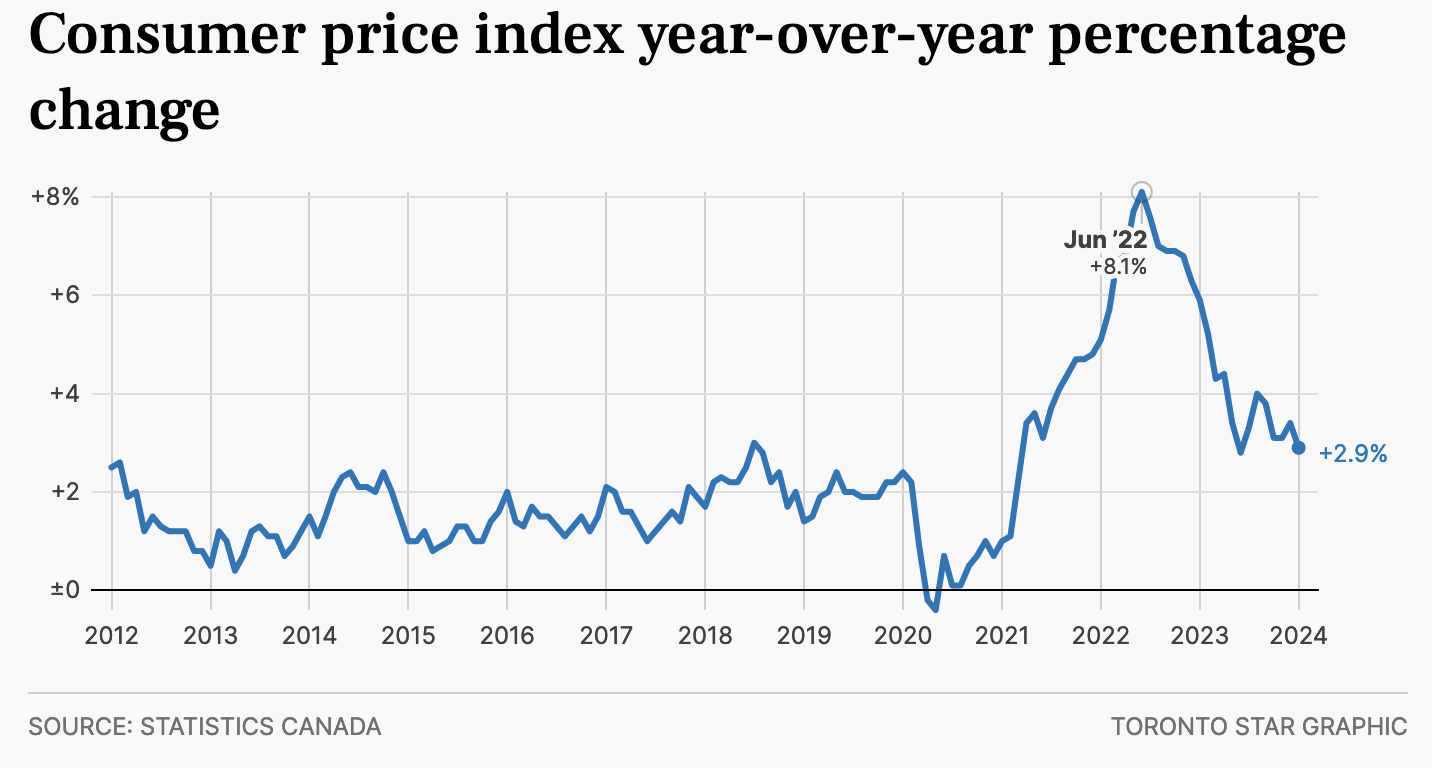

Canada’s January Consumer Price Index (CPI) report came in softer than expected at an annualized rate of 2.9%, down from 3.4% in December and 8.1% from the cycle peak in June 2022.

This brings the CPI within the Bank of Canada’s 1% to 3% target range for the first time since June 2023. The share of CPI components inflating more than 5% year-over-year fell to 24% from 68% at the cycle peak 2022. This good news on inflation boosted expectations for Bank of Canada rate cuts to start within the next four months; government bonds rallied, and stocks and the Canadian dollar sold off. See Rate cuts’ much more plausible’ as inflation takes unexpected dive in January.

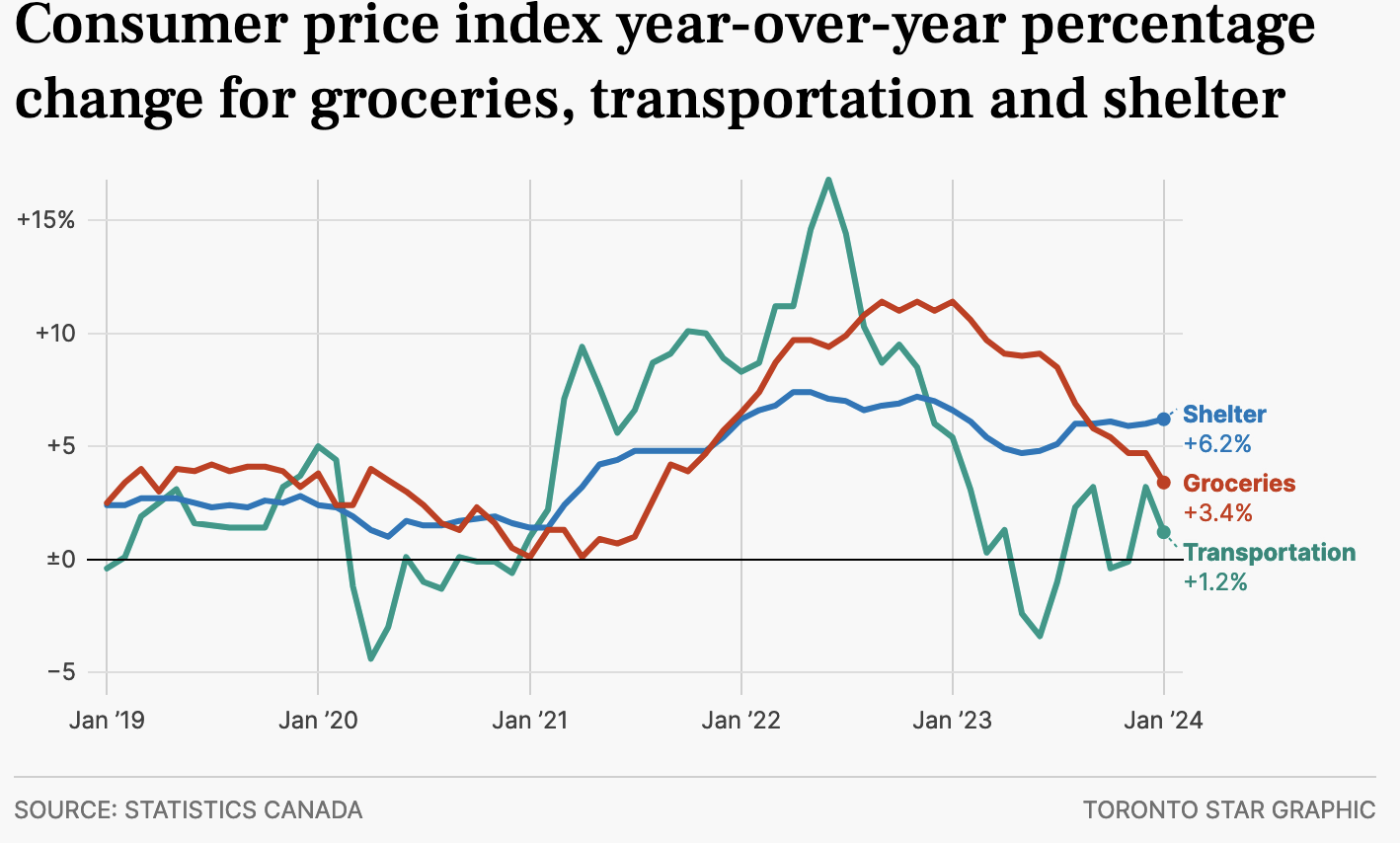

The trouble spot remains shelter. While other essentials like groceries (red line below since 2019) and transportation costs (green) show more subdued inflation, shelter costs are stubborn, rising 6.2% year-over-year.

The main driver of shelter inflation was mortgage interest costs (+27.4%)–the fastest-rising element of CPI. Higher carrying costs, which include interest expense, insurance, utilities and repairs, fed through to a 7.8% rise in rental costs.

As renewing mortgages meet higher interest rates, home prices stagnate and fall, and the room to refinance and pay for consumption or consolidate other debts has dried up. Canada’s outstanding mortgage credit climbed 0.3% to $2.16 trillion in December for an annual growth rate of 3.2% in 2023–the slowest 12-month appreciation since April 2001.

Meanwhile, credit card debt is rising at nearly 4x the growth rate of mortgage debt. Balances at chartered banks climbed 1.1% (+$1.1 billion) to $105 billion in December–a 12.6% increase from the same month last year. Canadian cards typically charge interest rates between 19.99% and 25.99%, causing unpaid balances to rise rapidly.

The trouble is that past interest rate hikes will continue to feed into higher carrying costs as mortgages come up for renewal in the months ahead, even after the central bank starts lowering overnight rates. If they panic and slash rates quickly, they risk magnifying a doom loop of reignited housing speculation and inflationary pressures.

This is the rock and hard place now facing Canadian policymakers. The economy became addicted to near-zero interest rates and counter-productive shelter inflation, and we now have no growth fallback plan to offset its necessary contraction.

Outstanding debt weighs heavy, and what cannot be refinanced or repaid is ultimately written down over time as collateral gets liquidated. This is why real estate downcycles typically take years, leading to the worst economic contractions.

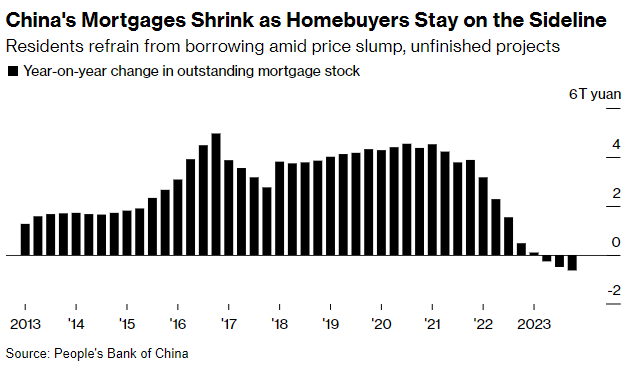

China is ahead of us in this cycle and offers a glimpse of how property bubbles deflate even amid easing efforts.

Chinese property prices have been tumbling since 2021, and household sentiment has soured. Despite lower prices, mortgage demand has contracted to the lowest on record (chart below since 2013, courtesy of Bloomberg).

This week, Chinese policymakers ramped up support efforts with the biggest-ever cut to a critical mortgage reference rate; lenders lowered the five-year loan prime rate to 3.95%. Still, easing news was met with little enthusiasm, raising expectations that lower prices and more aggressive measures would be needed. See China’s bold rate cut met with a lukewarm reaction.