April 23, 2023 | Can The Euro Be Saved?

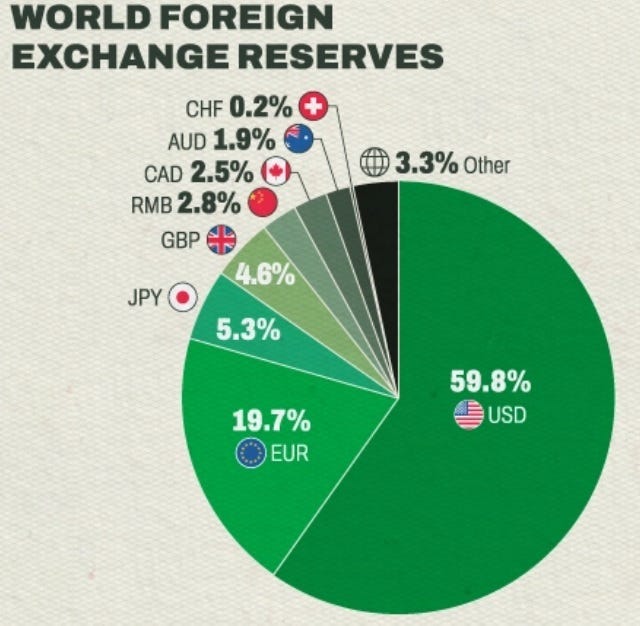

With all the talk about de-dollarization, this might be a good time to consider the world’s second reserve currency, the euro. Spoiler alert: It’s not a pretty picture, and Germany, believe it or not, is largely to blame.

It didn’t have to be this way

For most of the post-WWII era, Germany was the country that got it right. It didn’t hollow out its manufacturing base or crush its industrial unions. It made and exported advanced products, generating trade — and frequently even budget — surpluses. It ran clean, peaceful elections. Via the European Union and the euro common currency, it turned a continent of bloodthirsty micro-countries into a mostly peaceful confederation. And it backstopped the European Central Bank, leading investors to view Italian and Greek bonds as in reality German bonds, thus giving the weaker European economies a chance to adapt to a relatively sound-money regime. The euro, as a result, is now second only to the dollar as a reserve currency. Chart courtesy of Visual Capitalist.

But then it all went wrong.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel (a chief villain in this story) and her Christian Democratic party made a series of decisions that, um, didn’t work out as planned. The serious ones:

Imposing open borders. A key part of EU integration was free internal movement. Member country citizens could travel from, say, Berlin to Paris as easily as a US citizen can go from New York to Boston. But then — apparently at Merkel’s insistence — the EU decided to open its external borders and accept virtually all immigrants who showed up at any EU port of entry. Once in, newcomers had the same freedom of movement as EU citizens. A migrant who made it onto an Italian or Greek beach could arrive in London or Paris within days, and there was nothing the British or French governments could do about it.

The result? Massive and growing concentrations of newcomers who can’t find work and aren’t assimilating, and commensurately growing support for anti-immigrant political parties, many of which are also anti-euro. Here’s how French euro-skeptic Marine Le Pen did in last year’s election:

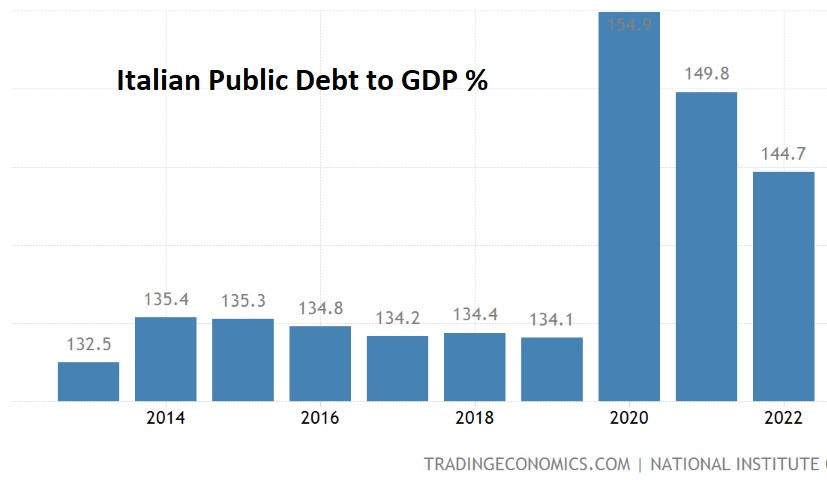

Allowing over-leveraged member countries to keep borrowing. Under the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, EU members were required to keep their budget deficits below 3% of GDP and government debt below 60% of GDP. Recall that the point of having the ECB buy up all those more-or-less worthless pieces of Italian and Greek paper was to give those countries a chance to meet these targets.

But Germany — the only eurozone member with the clout to impose fiscal discipline — never seems to have enforced its own rules. So the “PIGS” (Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain) just kept on borrowing, frequently (thanks to ECB bond buying) at rates lower than the US Treasury had to pay, creating an illusion of stability in a situation that was emphatically not stable.

The result: a bunch of insanely over-indebted countries with exactly zero chance of ever being able to deleverage, just waiting for rising interest rates or the next recession to bankrupt them.

Ditching nuclear power before replacements were ready. In the wake of Japan’s Fukushima nuclear accident, Merkel’s Christian Democrats decided to phase out nuclear power in favor of solar, wind, and Russian natural gas.

Since then, wind and solar have underperformed in not-very-sunny-or-windy Germany, and Russian natural gas (surprise!) evaporated after the US committed an act of war against both Germany and Russia by blowing up the NordStream 2 gas pipeline.

Germany’s last nuclear plant was just mothballed, leaving it with the above mix of inadequate energy sources. Its industrial base — upon which the whole European project depends — is threatened with extinction due to high energy prices and uncertain supplies.

Putting an exclamation point on Germany’s self-immolation, as the last nuclear plant closed, the affected utility raised its power rates by 45% to reflect its new cost structure.

And then there’s the demographic time bomb…

Believe it or not, the above problems, while more immediate, might be less serious than the Continent’s plunging birth rates. Only a handful of the major European countries are reproducing at rates high enough to keep them from eventually fading away. Germany, according to demographer Peter Zeihan, is beyond the point of no return.

Breakup?

So, the euro is facing soaring debt, political turmoil, a hobbled German industrial base, and demographic decline. Yep, not a pretty picture. And certainly not conducive to other countries viewing the euro as a safe haven asset.

Here’s the break-up scenario: Rising inflation forces the ECB to raise rates, which makes borrowing prohibitively expensive for the most overindebted eurozone countries. Under the threat of bankruptcy, they drop the euro and return to — and immediately devalue — their old currencies. The eurozone either reforms around a smaller core or disbands completely. Either way, the turmoil diminishes the euro’s reserve appeal.

The beneficiaries: Gold and the dollar in the short run, and gold-backed currencies further out.

STAY INFORMED! Receive our Weekly Recap of thought provoking articles, podcasts, and radio delivered to your inbox for FREE! Sign up here for the HoweStreet.com Weekly Recap.

John Rubino April 23rd, 2023

Posted In: John Rubino Substack

Next: Sentiment »