January 8, 2023 | What to Expect as Inflation Cools

[The following went out in mid-December to clients of Doug Behnfield, a Boulder-based wealth manager and senior vice president at Morgan Stanley. The letter provides an insightful view of the economic landscape as we enter the new year. Doug foresees falling stocks, falling inflation (or possibly modest deflation) and a continuing rally in long-term Treasurys. He is one of the most successful investors I know, and also one of the wisest. I have featured his work here many times in the past and am grateful for the opportunity to share his timely thoughts with Rick’s Picks readers. I’ve substituted my own charts from Tradestation for the ones in the original report because they reproduce with greater clarity. Also, the irreverent picture above was my choice, not Doug’s. He was assisted in preparing the report by his son Max Behnfield, a financial advisor at Morgan Stanley; and by Amelia Guidi, vice president and financial advisor in Morgan Stanley’s Boulder office. RA ]

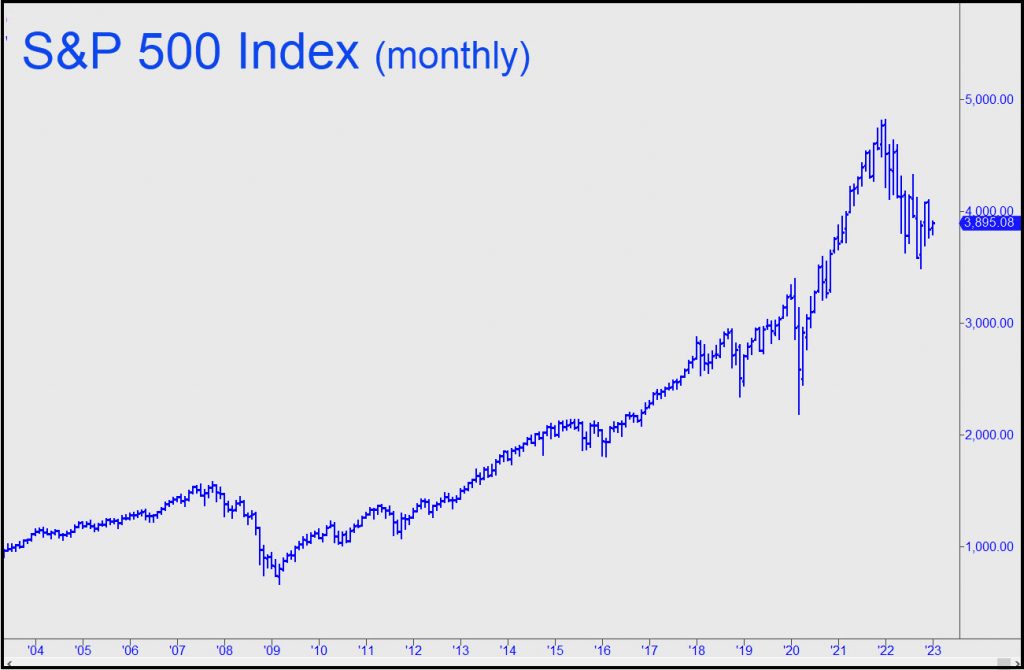

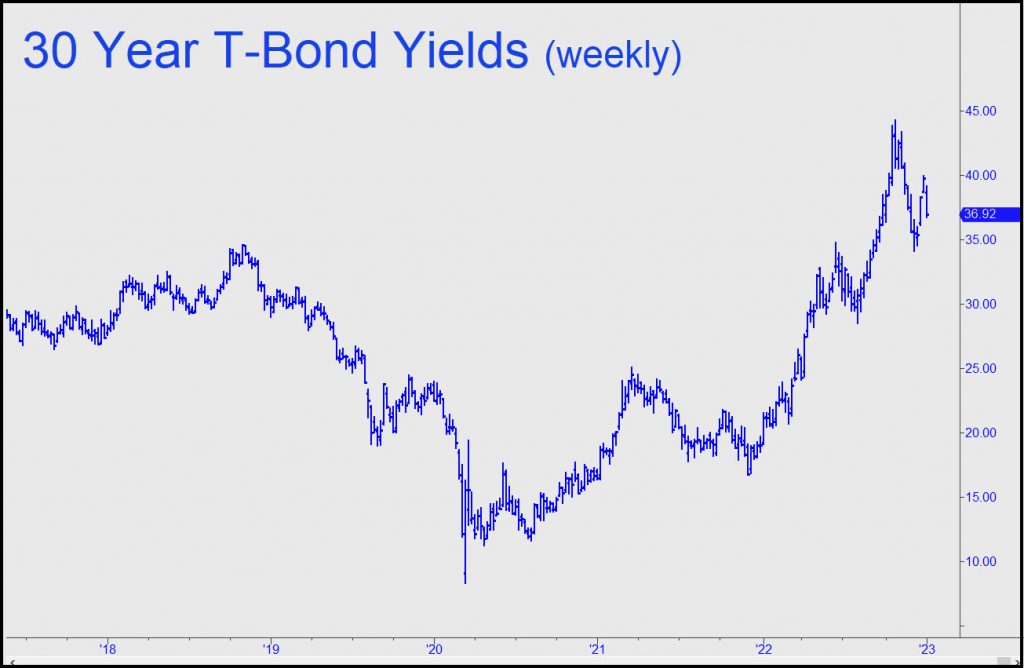

As we wind down a challenging year in the financial markets, there are many events that have occurred that shaped the outcomes that are much easier to see in retrospect. At this time last year, the stock market was making its last glorious run to all-time highsjust as Jerome Powell, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, was being handed the Keys to the City in terms of controlling inflation by President Biden. Powell immediately set out to alter the course of monetary policy that had been Fed Doctrine since 1987, when Alan Greenspan took over as Fed Chairman from Paul Volcker. What has happened since has been quite dramatic. Considering the very recent, downward reversal in long-term interest rates and the accompanying rally in the bond market, now seems like an appropriate time to chronicle what has transpired over the last year. The goal is to obtain a better understanding of what conditions are necessary to continue the recovery from the bear market in bonds going into 2023. In addition, the outlook for the ongoing bear market in stocks, as expressed by Mike Wilson, our chief investment strategist, is that it will continue to new lows early in the new year.

The Powell Pivot, 2021 Version

Although Jerome Powell became Fed Chairman in early 2018 during the Trump Administration, his first several years in the position were characterized by a serious lack of monetary policy flexibility. President Trump placed enormous political pressure on him to keep rates low in his first two years as chairman, and then the Covid lockdown and recession took over. It was not until his renomination by President Biden on November 22, 2021, that Powell received the full mandate and political capital to “maintain price stability”. By that time, he had a real problem on his hands.

The Great Post-Covid Inflation

By November 2021, consumer price inflation (CPI) had risen to 6.8% from 1.2% a year earlier. Up until then, the position of both the Fed and the Administration was that inflation was “transitory”. They had what appeared to be good reason to say that. “Base effects” had caused commodity prices, particularly energy, to soar. Gasoline prices, which had sunk to $1.77 in mid-2020 when no one was driving, had reached $3.40 per gallon. As a result of doubling in such a short time, gasoline became the most visible example of what had become a very serious political and economic problem.

“Inflation” had become the top reason for President Biden’s plunge in popularity. In addition, the plethora of Covid-related supply interruptions, particularly transportation bottlenecks and factory closures, were proving to be much more persistent than expected. This occurred in conjunction with the strength of the vaccination-led reopening of the economy and an excessive, scattershot approach to fiscal stimulus by the Federal Government. On December 2, 2021, Powell formally “retired” the word transitory. With that, comments from Powell and the other Fed governors became increasingly hawkish as they prepared the markets for a rate-hiking cycle. The Fed’s overnight rate had been stuck at 0% since the pandemic first struck in early 2020, so this hiking cycle has been painful in terms of increasing the cost of borrowing throughout the economy, not to mention the impact on bond prices.

Before the Fed had the opportunity to implement their first hike in March of this year, Russia invaded Ukraine in late February, precipitating a new round of supply interruptions. Oil and natural gas supplies from Russia were threatened and industrial metals and agricultural products from the region were cut off. In addition, the war itself, which represents an entirely different category of stimulative inflationary forces, promised to be a long one. The prices of commodities are more volatile than underlying fundamentals call for because of the enormous impact that speculative futures-trading can have. The chart below shows the price of crude oil going back two years. When Russia invaded Ukraine, oil prices exploded upward, exacerbating a wide array of rising CPI components. The thrust in crude oil prices lasted for a few months into June, but now they have receded to the lowest point of the year. So has gasoline.

Clearly, “base effects” work in both directions, a fact which tends to be obscured by such price volatility. In June, the CPI was peaking at 9.1%, but many of the Covid-related supply interruptions and base effects were beginning to wear off. Just as gasoline prices and the overall CPI reached its apex with the peak in crude oil prices in the first half of 2022, the subsequent dramatic decline, which is ongoing, will continue to exert a powerful deflationary impact on the CPI in the first half of this year. With the leading indicators of recession appearing all around us, the return to extremely low inflation, if not modest deflation, is likely to prevail in the year ahead. Morgan Stanley’s chief investment strategist, Mike Wilson, expects CPI inflation to plummet and 2023 to begin with stocks falling to new lows.

Clearly, “base effects” work in both directions, a fact which tends to be obscured by such price volatility. In June, the CPI was peaking at 9.1%, but many of the Covid-related supply interruptions and base effects were beginning to wear off. Just as gasoline prices and the overall CPI reached its apex with the peak in crude oil prices in the first half of 2022, the subsequent dramatic decline, which is ongoing, will continue to exert a powerful deflationary impact on the CPI in the first half of this year. With the leading indicators of recession appearing all around us, the return to extremely low inflation, if not modest deflation, is likely to prevail in the year ahead. Morgan Stanley’s chief investment strategist, Mike Wilson, expects CPI inflation to plummet and 2023 to begin with stocks falling to new lows.

The Asset Price Bubbles

Early last year, it was becoming apparent that the stock market was in a bubble. Conventional measures of valuation had become historically expensive, challenging, or exceeding the peaks in 1929 and 2000. Speculation was rampant. Crypto-related equities and “Meme” stocks were rallying and crashing, alternating between short selling by hedge funds and short squeezes by social media-driven day-traders. The price strength of the major indexes was dominated by “a handful of blue-chip names” and the largest capitalization stocks rocketed in the months leading up to Powell’s November 2021 reappointment. Securities-based credit and margin debt were reaching extremes as well.

In addition to the stock market bubble that was forming throughout 2021, a residential real estate bubble was inflating at a feverish pace. It is easy to look back on spring to see just how crazy it got. Listings were routinely met with multiple, above-asking price offers. “All Cash” offers and quick closings became the rule throughout the country. The hottest markets (Denver, Miami, Austin, Nashville, etc.) provided stories for the history books. “Affordability” became a non sequitur. Nationally, home prices rose over 46% from January of 2020 (before the pandemic) to the remarkable peak in this year’s 2nd Quarter. The mean reversion in home prices could dwarf the Great Recession decline that occurred between 2006 and 2012. Nationally, the decline in the Case/Shiller Index from the highs in 2006 to the lows in 2012 totaled 34%. The lion’s share occurred between mid-2007 through mid-2009 during the actual recession.

The “wealth effect” associated with double-digit appreciation in portfolio assets is an important consideration for the Fed when assessing the sources of demand and funding that impact inflation. More importantly, the amount of credit that can (and has been) created by the increase in collateral values that these asset markets represent can increase the money supply and result in more inflation. Chairman Powell has had to confront the wealth effect of these asset markets along with all the transitory Covid-related inflationary pressures.

Regime Change

In addition to conventional Fed tools like raising short-term interest rates, Powell apparently determined that the prior Fed doctrine of liberal and unconventional monetary policy actions aimed at the financial markets (like Ben Bernanke’s quantitative easing) had to change. He also had to “take the punch bowl away” from the asset-market craziness to prevent inflation from going out of control and resulting in further distortions in the economy. To do so, he will need to dispel the notion of a “Fed Put” for stock investors that began when Alan Greenspan took the helm at the Fed in 1987. This will likely be at the root of a “higher for longer” stance by the Fed during the “pause” stage of their policy. However, a longer pause is unlikely to interrupt the bond market rally we are currently experiencing.

In a recent edition of Breakfast with Dave, economist David Rosenberg cited several comments from Fed chairmen (and a Treasury secretary) that provide some historical context to the type of hawkish doctrine that Powell has established in place of the “Bernanke Doctrine” that he inherited in 2018. From Rosenberg:

Famous Last Words

Some central bankers and finance officials tell the markets exactly what is on their minds, and what they intend to do about it, especially when we are talking about excesses and imbalances in the markets and in the economy. Below I highlight key messages over time from officials that governed during gigantic bubbles — and they warned us well in advance what was in store. Andrew Mellon, Bill Martin, and Paul Volcker did not talk softly, but they carried a big stick — and bear markets occurred each time for the ensuing three years. The last quote was the warning Jay Powell delivered towards the end of last summer. Forewarned is forearmed:

“Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate. It will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up from less competent people.” • Andrew William Mellon, circa 1929

“If we fail to apply the brakes sufficiently and in time, of course, we shall go over the cliff […] in the field of monetary and credit policy, precautionary action to prevent inflationary excesses is bound to have onerous effects — if it did not it would be ineffective and futile. Those who have the task of making such policy don’t expect you to applaud. The Federal Reserve, as one writer put it, after the recent increase in the discount rate, is in the position of the chaperone who has ordered the punch bowl removed just when the party was really warming up.” • William McChesney Martin, October 19, 1955

“Meanwhile, insidiously our real economic performance, in the sense of productivity growth, has deteriorated. The one problem has contributed to the other. To break that cycle, we need to change expectations. One indispensable element in the process is singularly in the domain of the Federal Reserve — we must have a credible and disciplined monetary policy that is characterized by sustained moderation of growth in money. Alongside that policy we need to understand that real growth will depend on real performance — most of all to promote productivity, savings, and investment. When those approaches are built into our expectations and into our decision making, then our present intentions can more easily become tomorrow’s realities. We would truly have in place the elements of “sticking with it,” not just in 1980, but for many years beyond.” • Paul Volcker, January 2, 1980

“Restoring price stability will take some time and requires using our tools forcefully to bring demand and supply into better balance. Reducing inflation is likely to require a sustained period of below-trend growth. Moreover, there will very likely be some softening of labor market conditions. While higher interest rates, slower growth, and softer labor market conditions will bring down inflation, they will also bring some pain to households and businesses. These are the unfortunate costs of reducing inflation. But a failure to restore price stability would mean far greater pain.” • Jerome Powell, August 27, 2022

In each instance, these leaders were tightening monetary conditions to remove leverage from the economy. High levels of debt, often in the financial markets, were behind the inflation that they were attempting to limit.In the current reality, Powell has been faced with the aftermath of unprecedented fiscal stimulus which was delivered broadly by the Federal Government to the consumer during the pandemic. On top of that, he faced twin bubbles, driven by extreme leverage and speculation, in both the stock market and residential real estate.

Fiscal stimulus is now fading, although it is being replaced with a dramatic increase in credit card and other installment debt among consumers. The parabolic moves in stocks and home prices have reversed, but so far, the “buy the dip” mentality left over from the preceding bubbles appears to be intact, at least for stocks. Along those lines, investment strategist Wilson is calling for a decline in the S&P 500 from the recent highs (4100) down to approximately 3000 between now and the 4th Quarter earnings season, which means much lower lows for stock prices during the 1st Quarter of 2023.

Even though CPI inflation has clearly reversed from the mid-year highs, the Fed is remaining hawkish by suggesting that there is more work to do by raising rates further and keeping them higher for longer. Time will tell. A lot will depend on how the stock and housing markets perform. A substantial market decline such as Wilson is suggesting would result in a significant amount of leverage being liquidated. That would add to the Fed’s sense of “mission accomplished”. (See Andrew Mellon’s comment above: “Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks…”).

As we get ever closer to the point at which the Fed is done raising rates, the process of switching from tightening ti easing is referred to as the Fed Pause, which begins with the first meeting without a hike in the cycle. Next is the Fed Pivot, which begins with their first actual rate cut. Historically, long-term bond yields have peaked near the pause, and they typically decline throughout the series of rate cuts that occur after the pivot. Declining rates are synonymous with a bull market in bond prices. For example, in the last cycle, the Fed’s final hike occurred in mid-December 2018. The pause therefore began with the February 2019 meeting at which they did not hike. Bond rates peaked ten weeks earlier, in early November 2018. Bond rates dropped (and bonds rallied) to the bottom of the 2020 recession.

Finally, the peak in rates that we just experienced in late October appears to be decisive. The extent of the decline will be determined by several factors. A substantial decline in inflation that is accompanied by a Fed pivot from rate hikes to rate cuts is typically the condition that correlates most with bond market rallies. In addition, garden-variety, post-WWII recessions have been deflationary events in which rates decline meaningfully.

STAY INFORMED! Receive our Weekly Recap of thought provoking articles, podcasts, and radio delivered to your inbox for FREE! Sign up here for the HoweStreet.com Weekly Recap.

Rick Ackerman January 8th, 2023

Posted In: Rick's Picks

Next: Stirring the Pot For War »